A&P Intertrust, a Canadian company with a website in English and Russian, offers the opportunity to set up a company in the British Virgin Islands for $900 (£638) up front and $870 for every subsequent year. OffshoreCompanyCorp will do it for $569 for the first year, and $969 thereafter.

Healy Consultants will provide a more comprehensive, one-week setup service, for an average cost of $5,950 for the first year. As part of that deal, the company will help the client set up an international bank account. In its literature, Healy promises to “shelter our client from the associated administrative challenge” of opening an account.

More than 40 per cent of all offshore companies are incorporated in the British Virgin Islands, where secrecy laws mean that company owners are shielded from scrutiny. Those companies include, according to a massive dataset leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalism from a Panamanian law firm, Mossack Fonseca, nearly 115,000 entities linked to public figures, from heads of government to music moguls.

“I think the major thing is the identities,” says Tommaso Faccio, a lecturer in accountancy at Nottingham University and a former advisor to multinationals on international tax issues. “We already knew that the elite of this world, and the very rich of this world, were hiding stuff in these offshore accounts.”

The fact is that any individual can hide behind a corporate veil, they’re basically given legal ways to hide their money

Using these structures is legal. However, their secrecy means that offshore jurisdictions have been exploited to harbour criminality, from laundering drug money through London property, to hiding the proceeds of state corruption in Nigeria. Although the practices revealed by the Panama Papers are well known, the leaks have exposed the sheer scale of the use of shell companies.

As Faccio says: “This was the fourth-largest company just in Panama. There’s at least three more that do the same for at least as many people. And then there’s probably one Mossack Fonseca in every tax haven.”

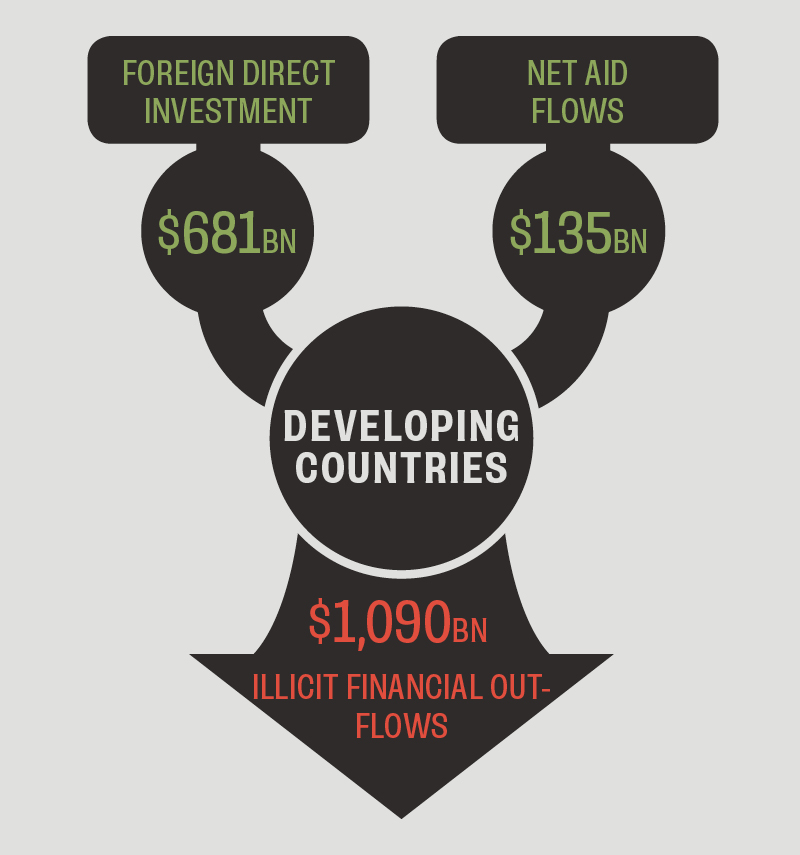

The opacity of this level of global finance has real implications for societies, with impacts that range from driving up property prices in London to gutting the national resources of developing countries. In March, an investigation by Transparency International found that more than 36,000 properties in London are owned by offshore shell companies; according to estimates by Global Financial Integrity, more than $1 trillion a year moves moves illicitly out of developing economies via tax havens.

“This is all interconnected,” says Tom Cardamone, managing director of GFI. “The fact that $1 trillion leaves developing country economies a year, it’s got to go some place.”

Fixing the problem is likely to be one of political will, although the leaks show how deeply interconnected political and financial elites are. There has been some movement over the past few years. From 2017, most tax havens have agreed to share some financial data, although there are holdouts, including Panama, which is unwilling to sign up to a treaty unless every other country does so.

In the wake of the Panama Papers furore, the UK, France, Spain, Italy and Germany have announced new rules that may force the ‘beneficial owners’ of shell companies to be identified. Cardamone believes that this would be a critical first step.

“The fact is that any individual can hide behind a corporate veil, they’re basically given legal ways to hide their money,” he says. “This is going to continue until the global community gets the political will to eliminate anonymous shell companies.”

Tricks of the trade

How to use a tax haven to duck the taxman

Laundering the proceeds of state corruption

A Nigerian government official cuts an off-the-books deal with an international company, which siphons money into a Swiss-held slush fund and pays it to a shell company in the BVI. That anonymous BVI shell company, owned secretly by the government official, buys a high-value property in London, which it then sells after a few years, turning the dirty money into clean money, which it then stuffs back into a Swiss bank account.

Avoiding capital gains tax in China

A Chinese businessman makes a few million in the local property market, and invests it all overseas in a new venture — an exciting opportunity in the Cayman Islands. That anonymous Cayman Island company then invests in another Cayman Island company, which in turn invests back into China, getting tax breaks for bringing in overseas money.

Tricking the taxmen

A British company in Kenya drills for oil. It sets up a local subsidiary and another company in Bermuda. The Kenyan subsidiary sells the oil to the Bermudan company at a very low price. As far as the government of Kenya is concerned, there is little profit to be taxed. The Bermudan company sells the oil to the parent at a price close to the market value of the oil, so the UK tax authorities see another company barely scraping by. The money stays in Bermuda.